CHAPTER V.

PRINCIPALITY, SUBORDINATION, AND COMPLEMENT OR BALANCE IN PAINTING, SCULPTURE, AND ARCHITECTURE

General illustrations of the effects of the three methods—

Principality by size, position, direction of lines, color, and shading—

Illustrations—

In Sculpture—

In Architecture, through a Porch, door, window, dome, Spire, etc.—

Vertical and horizontal balance—

Complement between principal and subordinate features—

Between the subordinate, with the principal separating them—

Groupings of odd and of even numbers—

Complement and balance in painting—

In Sculpture—

in Architecture—

Approaching symmetry in large public buildings which demand Effects of dignity—

Principality and complement in modern public buildings—

Criticisms—Suggestions—

Even and odd numbers in the horizontal and vertical arrangements of architecture.

The importance and relationship of principality, subordination, and balance or complement are much more apparent in the arts of sight than in those of sound. Ruskin, in his “Elements of Drawing,” Letter III., illustrates these effects, although he applies what he says only to principality, by drawing certain groups of leaves

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 13

“a”, he says, “is unsatisfactory, because it has no leading leaf; b is prettier, because it has a head- or master-

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 069]

leaf; and c more satisfactory still, because the subordination of the other members to this head-leaf is made more manifest by their gradual loss of size as they fall back from it.” To this may be added a fourth figure, d, with the declaration that it is unsatisfactory because it contains nothing to complement or balance the lower leaf.

Sometimes, in art, the principal object is brought into prominence by being made larger than the subordinate objects. This was the old Egyptian method. According to Miss Edwards, in her “Thousand Miles up the Nile,” in the pictures still remaining in the tomb of Ti, near the site of ancient Memphis, the figures of the principal character are, in all cases, about eight times as large as those of the servants represented as at work around him. Of the same nature is the representation in this Fig. 14,

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 14 – Piankli Receiving the Submission of Namrut and Others.

(See pages 70, 189)

of “Piankli, Monarch of Napata, Receiving the Submission of Namrut, the Hermopolitan King.” This king is depicted in the small figure in the upper line at the right as leading a horse with one hand, and holding in the other a sistrum, which it was customary to carry when approaching a god. In the line below, those who have

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 070]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

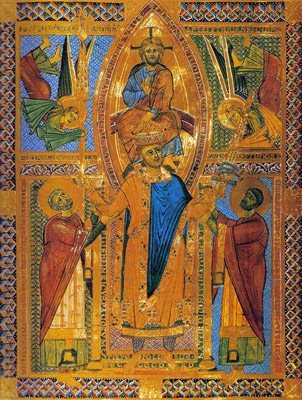

Fig. 15 – Henry II receives from God the crown, holy lance, and imperial sword.

(From “Henry’s Missal.”)

(See pages 72, 189)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 071]

been conquered are depicted in a more slavish attitude. An effect of a similar kind is produced at the expense of making the divine being himself subordinate, in Fig. 15, page 71, taken from the German “Henry's Missal.” Sometimes, as in some of the “Madonnas” of the old masters, the principal figure, though no larger in itself, is made to have a larger effect by being elevated on a throne or in clouds. See the “Madonna” by Fra Bartolommeo, Fig. 58, page 185, also Raphael's “Transfiguration,” Fig. 46, page 147. Sometimes this figure is in the foreground, as the gladiator in Gerome’s “Pollice Verso,” Fig. 26, page 81, or as the central character in Raphael’s “Ananias,” Fig. 94, page 288. Sometimes, in connection with these other methods, the leading outlines of pictures are made to radiate from the chief figure, as from the Christ in the air, in Raphael’s tapestry of the “Conversion of St. Paul”; or from the gladiator in Gerome’s Pollice Verso” Fig. 26, page 81; or from the Desdemona in Becker’s “Othello,” Fig. 55, page 181. Sometimes a figure is made most prominent by a use of color, as by red drapery given to the Christ in Titian’s “Scourging of Christ”; and sometimes by a use of light and shade, the former being concentrated where it will necessarily attract attention.

In Rubens’ “Descent from the Cross,” Fig. 16, page 73, a white sheet, the whitest object in the picture, is placed behind the form of the Christ. In Correggio’s “Holy Night,” Fig. 70, page 2I5, all the brightness in the picture is reflected from that which illumines the face of the infant Jesus. It is needless to say at what the spectator looks first when viewing these works. He at once recognizes the principality of the form about which all the light is massed. They are admirable instances, therefore, of how the most successful results of both principality

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 072]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 16 – Descent from the Cross, by Peter Paul Rubens.

(See pages 16, 72, 80, 144, 190, 214, 235, 257.)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 073]

and massing, to be considered presently, can be secured when the two operate conjointly. In sculpture the methods under consideration are equally prevalent and effective. When there are many figures, the same principles apply as in painting, excepting, of course, cases where there is color. See the relief, now in the Louvre, entitled “Mithras Stabbing the Bull,” Fig. 54, page 179.

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 17 – Statue of Leda at Florence.

(See pages 74, 85, 179, 289)

When, either in painting or sculpture, the whole work contains but a single figure, the relative prominence of merely different parts of this, must show the influence of these methods. “The Leda,” from the statue at

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 18 – Statue of Titus, in the Louvre

(See pages 75, 85, 120, 180, 289)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 074]

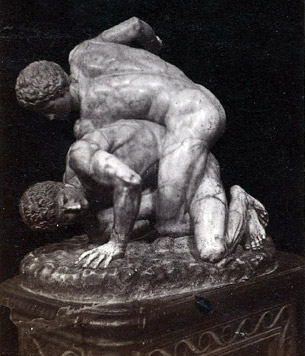

Florence, Fig, 17, page 74, with the hand before the breast, about which also all the outlines of the unresisting form seem to centre, gives principality to the heart, the seat of the affections. The erect head on the thick neck and broad shoulders of the “Titus” in the Louvre, Fig. 18, page 74, in connection with the commanding gesture, gives principality to these, the seat of the directing power, or of authority. The equally erect but more buoyant figure of the “Diana” of the Louvre, as she speeds to the chase, Fig. 19, gives principality to the mental purpose subordinating to itself every tendency to mental weariness. The “Mercury,” found at Herculaneum, Fig. 20, page 76, with head bending toward the trunk and limbs, shows the mind subordinated, but, owing to his evident reluctance, only temporarily subordinated to the bodily condition. In a different way, because devoid of any suggestions of mental opposition, the positions of “The Wrestlers,” Fig, 21, page 77, make everything subordinate to lower physical strength.

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 19 – Diana, from the Louvre

(see pages 75, 85, 120, 186)

photo credit: Eric Gaba (Wikimedia Commons)

In architecture, principality is attained by making prominent a porch or door, Fig. 1, page I5, indicating per-

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 075]

haps the numbers, great or small, expected to enter it; or a window, Fig. 22, page 78, or dome, Fig. 42, page 123, indicating the amplitude or height of the interior halls; or a spire, Fig. 68, page 207, indicating an intent to attract

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 20 – Mercury. (Bronze from Herculaneum)

(See pages 75, 85, 120)

attention from a distance. Sometimes all these features together are emphasized by being all made to constitute parts of one principal tower, Fig. 71, page 218. The impression of completeness that many people derive from

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 076]

buildings like the Oriental mosques, Fig. 3, page 19, Fig. 31, page 88, Fig. 42, page 123, or “St. Peter's” at Rome, Fig. 23, page 78, is owing undoubtedly to the fact that the dome used in them as a principal feature is especially effective in subordinating to itself all the other forms, and giving to the buildings as wholes an appearance of unity. In many structures extending into wings that equal or

Fig. 21 – The Wrestlers.

(See pages 75, 85)

surpass in size their central connecting parts, Fig. 24, page 79; or containing large numbers of openings, gables, turrets, domes, or spires equivalent in effect, Fig. 72, page 221, no such impression is produced. Nor, for reasons to be given farther on in this chapter, can one claim that in villas, such as are represented in these figures, this impression always should be produced. In neither building is any special dignity of treatment demanded. Be-

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 077]

sides this, we have in Fig. 24, page 79, a twin effect allowable in a building of such a character, and in both it and Fig. 72, page 221, an effect of interspersion, to be considered in Chapter XIV. But, while these statements are true, it remains a fact that any lack of principality in any building appears to some to be a defect, although, as is often the case in such matters, they

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 22 – Houses of Parliament. From Old Palace Yard.

(See page 76.)photo credit:

damo1977 (Flickr)

may not be able to explain why its appearance is unsatisfactory.

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 23 – St. Peter’s, Rome.

(See pages 18, 77, 87, 96, 124, 186, 207, 265.)

Passing now to compliment and balance in the arts of sight, we had better start with their most elementary manifestations. There are two way of placing two objects together in space. The one may be partly or wholly under the

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 078]

other, or the two may be side by side. In the former case, they seem to fulfil the requirements of balance, or to have equilibrium, whenever the lower object appears larger and therefore stronger than the upper, —a condition which we have all seen carried out in the increased size given to the base of a monument. See statues mi Fig. 41, page 121. But in the latter case, when the two are side by side, balance seems to be preserved, notwithstanding a reasonable degree of difference in their relative sizes, whenever they appear to be exactly upon

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 24 – A twin villa.

(See pages 77, 78, 79, 123, 124, 187)

the same level horizontally, as they would be if floating in the water, lodged on the ground, or suspended, when of equal weight, in scales.

Sometimes two factors thus balanced include all that an art-form contains; and this, of itself, is often satisfactory without any principality. In fact, in such cases, we may say, perhaps, that the twin effect itself has principality. Notice the “Investiture of a Bishop by a King,” from the codex in St. Omer, Fig, 25, page 8o; “The Twin Villa,” above, and the “Gate of Serrano, Valencia,”

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 079]

Fig. II, page 47. There are ways, however, in which, even where there are but two factors, one of these can be made principal, and the other subordinate as well as complementary. If they be the figures of two persons, one can be tall, or elevated, or standing, while the other is short, or sitting, or lying down (see the gladiator and

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 25 – Investiture of a bishop by a king. (From a codex in St. Omer.)

(See pages 48, 79)

his antagonist in Gerome’s “Pollice Verso,” Fig. 26, page 81,) or one can be in the light, and the other in the shade. See, again, Fig. 16, page 73, and Fig. 70, page 215. If, in addition to the two, the form contain an odd feature, the two can continue to seem to balance, in case the odd be placed between them. In fact,

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 080]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 26 – Pollice Verso, by Gerome.

(See pages, 16, 30, 72, 80, 82, 144, 172, 179, 182, 186, 217, 239, 257.)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 081]

arrangement augments the effect of balancing, by that which, as we shall presently find, is the main characteristic of symmetry; for, so placed, the odd feature acts like an intersecting line, clearly showing—as the body does between the wings of a bird, or the head between the shoulders, or the nose between the eyes—just how the pairs are separated and related.

The same is true of groups, too, formed of five and seven, or of any other odd, rather than even numbers. Only when there are sufficient factors to make it difficult to count them in a single glance, is it as easy to secure effects of balance with the latter as with the former (see Turner's “Decline of Carthage,” Fig. 51, page 175). When there are many figures, as in the one hundred and sixty of the size of life in Paul Veronese’s “Marriage at Cana,” or in the two hundred and ten, thirty of which are of full length, in Tintoretto’s “Paradise,” there is usually a principal group containing a principal figure, and many subordinate and complementary groups, each, at times, containing its own principal figure. Of course, the groups thus formed are usually arranged as if they were only individual factors. Notice the grouping in Raphael’s “Transfiguration,” Fig. 46, page 147, and in Teniers’ “Village Dance,” Fig. 43, page 143.

The numbers of ways in which effects of balance may be secured in these visible arts, especially in painting, seem practically infinite. As a method, too, it is almost universal. In Gerome’s “Pollice Verso,” Fig. 26, page 81, a gladiator’s limbs stretched upon the ground on one side of his triumphant antagonist is exactly balanced by the armor that has been stripped from them, which lies on the other side of the victor; while the arm of the latter, lifted that his sword may strike, is balanced by his victim's arm

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 082]

lifted to appeal for mercy. In the first case, we have an instance of balance produced in spite of decided contrast between the balancing members. A similar effect is produced by color in one of Paul Veronese’s pictures of the

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 27 – The Discobolus, or Quoit Thrower.

(see page 85)photos credit:

Matthias Kabel (Wikimedia Commons)

“Marriage at Cana,” where a small black head of a dog on one side is said to balance a large mass of black on the other side. So, too, in Jules Breton’s “Brittany Washcr-women,” formerly in the New York Metropolitan Museum,

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 083]

a little blue in the women’s skirts balances a much larger amount of blue in the sea opposite to them.

As exemplified in the human figure, and so in sculpture, balance can never be fully understood, except as it is treated in connection with both symmetry and proportion. Here it is sufficient to point out that, as a rule, in order to secure variety, the limbs of the two sides of the body should be in somewhat different positions. If this arrangement be adopted, nature requires that a man should keep his equilibrium, and art that he should seem to keep it by

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 28 – A small house.

(See pages 85, 96, 124, 187.)

making an exertion in one direction sufficient to counteract that made in the other. For this reason, when one is gesturing, or appearing to gesture, his hands and head, if the latter be not kept still, should make counteracting movements. The head should move toward the hands when they are lifted, and away from the when they fall. Or if he be posing, and his arm be thrust out on one side of him, his other arm, or his trunk or foot should be thrust out on his other side, sufficiently at least to secure an effect of equilibrium. The necessity in art of seeming

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 084]

to carry out such requirements, especially where postures are unusual, as in the case of the “Discobolus,” (Fig. 27, page 83) presents one of the greatest difficulties which the sculptor has to encounter. See statues on page 74 to 77.

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 29 – Palace of Justice, at Lyons, France.

(See pages 87, 96, 261.)

In architecture, it is possible for one subordinate feature to complement the principal, as a wing, or porch, or door at one side of a house balances the whole facade of the building to which it is attached (Fig. 28, page 84); or as

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 085]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 30 – Suleymaniya Mosque, 1556.

(See page 90.)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 086]

a tower at one side or corner offsets the body of a church (Fig. 97. page 292); or as a dome completes that which supports it (Fig. 23, page 78). With exception of the dome, however, such arrangements are in place mainly in smaller buildings in which graceful and picturesque effects are desirable. In all such cases, too, it is important that the subordinate feature be sufficiently large to be a true complement or balance. A wing, or tower, or dome of any kind, too small for that which goes beside or beneath it, is invariably unsatisfactory. Notice the absence of effectiveness for both these reasons in the cupola surmounting the unnecessary mixture of styles in the “Palace of Justice,” at Lyons, France, Fig. 29, page 85.

In the degree in which a building, like a church, a court-house, or a school, is to be devoted to a serious purpose, it should convey an impression of dignity. In art, as in life, this effect results from an appearance of perfect equilibrium. In architecture it is secured in the degree in which the principal entrance is exactly in the middle of the facade, with an equal number of subordinate features, towers, pillars or openings, as the case may be, on either side of it. Notice, as exemplifying this arrangement, “Cologne Cathedral,” Fig. 2, page 17, the “Taj Mahal,” Fig. 3, page 29, “St. Mark's, Venice,” Fig. 31, page 88, and “The Gate of Serrano,” Fig. 11, page 47. In the Greek temples, the front peristyle—to which, as a whole, was given principality—always contained an even number of columns, in order that, before the central door, there might be a central space between them. This space, too, was wider than that between the other columns, and the spaces between the columns farthest to right and left were narrower than those between any others. Thus, in the principal feature considered in itself, the Greeks

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 087]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 31 – Church of St. Mark, Venice, with Campanile.

(See pages 18, 77, 87, 90, 96, 124, 180, 186, 190, 207, 261, 262.)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 088]

secured the effect of symmetry through that of principality with balance. See “Temples of the Acropolis,” Fig. 1, page 15.

Our own architects have wisely ceased to imitate the Greeks in cases where to do so would be out of place; but the principle of imitation has had, and continues to

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 32 – Canterbury Cathedral, from Southwest.

(See pages 18, 77, 90, 124, 207, 261.)

photo credit: Hans Musil (Wikipedia Commons)

have, such an influence, that, as applied to the Gothic, we still cling to methods that represent not its best, but its worst phases. The tower at one corner, or at the side, which is so common with us, is an inartistic adaptation of what had a very different effect when separated from the church in the structure called a campanile (See an Ori-

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 089]

ental example of this in Fig. 30, page 86, and a more familiar one in Fig. 31, page 88. Nor can a huge tower or towers placed at the front (see Fig. 2, page 17) fulfil at all the same office as that much smaller in proportion which are kept subordinate to a tower or dome at the centre (see Fig. 32, page 89). There is no doubt that the ideal building is represented not in Fig. 2, page 17, but by the way in which principality, subordinateness,

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 33 – Iffley Church.

(See pages 92, 124.)

and complement are all given their due proportionment, as in Fig. 32, page 89.

Besides imitation, the desire to have a building present an impressive appearance on the street is accountable for this accumulation of the chief features on one side or corner. But many of these buildings are on two streets; and the demands of the ordinary American church are so different from those of the European that, it is strange that our architects, in the arrangements both of exteriors and

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 090]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 34 – Shadyside Presbyterian Church. (Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge, Architects.)

(See pages 92, 96, 124, 186, 190.)

photo credit: Tim Engleman (shadysidelantern, Flickr)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 091]

interiors, have not been forced into more originality. There are undoubtedly good reasons why that which artistically considered, is the most satisfactory form of the cathedral and parish church, Fig. 33, page 90, should not be adopted by us. Such a building is difficult to construct; and, when constructed, the huge foundations of the tower interfere with both hearing and seeing. Yet an adaptation of the form to modern purposes, as well as an artistic building in all regards, seems to be furnished, so far as one can judge from a photograph, in the “Shadyside Presbyterian Church,” Fig. 34 page 91.

As a rule, however, an American church has two separate parts—one devoted to worship, and the other, mainly, to the Sunday schools. In some cases, with admirable effect, a tower has been placed between these parts. But the idea thus given form could be further developed, and the building as a whole made more distinctly a unity. The tower could be back from the street, and in the centre of the structure: and under it could be not only the central entrance, but an entrance-hall as long as the building's width, broad, lofty, and imposing, and filled, as time passed on, with memorials. The main audience-hall, too, if architects and those who employ them would only subordinate their traditional notions to the dictates of taste and reason, could be made much more original and artistic, as well as convenient and practical. See Fig. 35 Page 93, and Fig. 36, page 94, the work of Mr. G. H. Edbrooke, of New York.

The same statements apply, of course, to schools and all kinds of public edifices. It is remarkable, by the way, that those who have planned modern cathedrals have not recognized the propriety of placing the central tower

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 092]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 35 – Plan for a church – Exterior.

(See page 92.)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 093]

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 36 – Ground plan for same church.

(See page 92)

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 094]

entirely over the nave, instead of at the juncture of the nave and transepts. In the former place, the tower could be narrow enough to prevent any structural weakness owing to a reach of arches under it, and, if it were there, it would be possible to have in front of the chancel, in connection with all the traditional effects of nave and aisles and chancel, a large audience hall, flanked, if necessary, by wide transept galleries, in which the crowds in attendance could not only hear but see the services. As such a hall is acknowledged to be almost essential to a modern church of any kind, one would suppose that the first effort of architects would be in the direction of a design in which it could be embodied without difficulty. Notice Fig. 37

[click here to enlarge image]

[click here to enlarge image]

Fig. 37 – Ground plan for a cathedral.

Before leaving this subject, it may be well to add that what has been said of the method of emphasizing both principality and complement through the use of uneven

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 095]

rather than of even numbers, may apply to perpendicular as well as to horizontal arrangements. To one looking upward at a building, for instance, the basement often seems to complement the roof, or a first story to complement a third; while the principal part, or, at least, the pivot-line of balance, seems to be between them. It is worth noticing in this connection, too, that the Greeks, according to all testimony, almost invariably grouped different architectural features, whether placed perpendicularly or horizontally, according to proportions determined by odd numbers, 1, 3, 5, 7, etc. and also the fact, which our own experience has probably confirmed, that the majority of men feel that a house or tower having an equal number of openings or divisions of spaces either horizontally or perpendicularly—say exactly two or four windows on a story, or two or four stories with no apparent basement or roof—is less pleasing than a house having three or five windows on a story, or having one and one half, two and one half, or three or five stories, or four stories with an apparent roof. See Figs. 3, page 29; 11, page 47; 23, page 78; 28, page 84; 29, page 85; 31, page 88; 34, page 91; 42, page 123, etc.

[The Genesis of Art-Form by G.L. Raymond, chapter V, page 096]